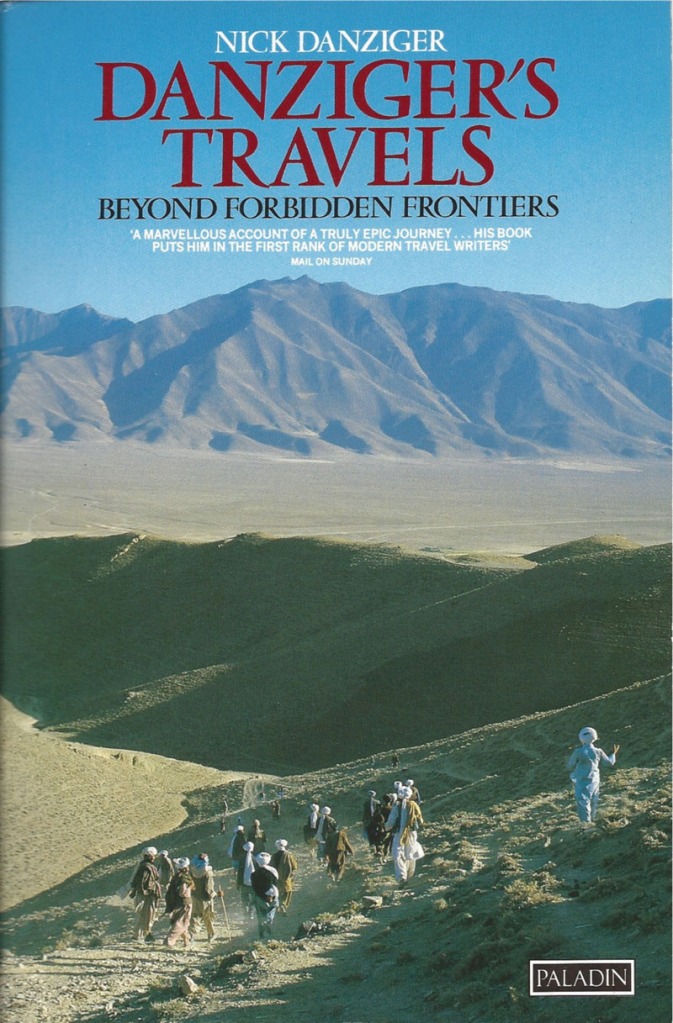

I first came across Nick Danziger through his book, Danziger’s Travels-Beyond Forbidden Frontiers. A personal account of his travels along the Old Silk Road, a trading route that goes through Asia. In the mid-1980s, Nick graduated from Chelsea Art School, applied successfully for a fellowship with the Winston Churchill foundation and made his way through Europe, to Iran, Afghanistan, Tibet and China. Along the way, he had some amazing adventures and took lots of great photographs as well. His diaries of the time became the best-selling book ( first published in 1987) and in his words, it became the first stepping-stone in his career. Today he is an acclaimed photojournalist and film-maker. In April he visited London on a flying visit and we talked about his work, his career and his thoughts on self-publishing, social media, research and the value of editing amongst other things.

Tom Broadbent: Well I’m sitting here with Nick Danziger, who hardly needs any form of introduction but for the record he’s a photographer, a filmmaker, a writer, a storyteller, a humanitarian. Is that about right Nick?

Nick Danziger: More or less, a bit more and a bit less.

T: I can’t promise Desert Island Discs levels of journalism (Nick was on in 2003) but I thought we could have a chat about your career and what you’re up to at the moment. You first contacted me through LinkedIn, saying that we knew a lot of the same people and that we should hook up. Which I thought was quite interesting. I was like, really?? Yeah we do, we do Nick!! You mentioned that you were working on a new book called Back to the USSR: Heroic Adventures in Transnistria which you’ve put together with the travel writer, Rory MacLean so tell me about that.

N: Well it’s become incredibly topical now because a lot of the people in Crimea and indeed international journalists are all using Transnistria as an example that Crimea is following so I went to Transnistria a couple of years ago and it was incredibly fascinating because here is a self declared breakaway republic within a breakaway republic. But they haven’t moved away from the times as it were of the USSR hence Heroic Adventures in the USSR because they still look to Lenin, Stalin. They went to be part of the Soviet Union, even though the Soviet Union is long gone. But they’d like a re-attachment to Russia so it’s a small territory but none the less both agrarian and rural and urban and city-dwellers. It was a really fascinating journey because being able to see something of people’s lives. It’s difficult to get to Transnistria in terms of them allowing people, particularly foreigners to have access to the country and for them to travel around as well. So all in all it was interesting then and it’s become a lot more interesting and topical now. We crowd-sourced the book, so I don’t know if you want to talk about that?

T: Yes I do.

N: It was a bit of a struggle in the beginning but now we’re fully financed, but there’s still time to sign up and get your name in the book.

T: So Transnistria, where is it?

N: It’s between Moldova and Ukraine so it’s Eastern Europe. It’s landlocked and it’s the other side of the Nistra river hence the name Transnistria. They had a war of secession, which resulted in several thousand deaths. But they’re not recognised by anywhere, anyone rather. They are as it were, heavily subsidised by Russia. They couldn’t continue to function without Russian assistance.

T: You’re obviously engaged with crowd funding to finance the book and you made a really brilliant launch video for it, which is a shining example of what all crowd funders should do. A funny, if that’s appropriate, video to launch a project. One thing that came out of that was how hospitable the people of Transnistria are.

N: A lot of drinking.

T: My question is how drunk did you get in the making of this project?

N: The funny thing about it all was that everyone we went had a kind of remedy so that we wouldn’t be drunk so one day we were told this fish soup you know, you’ve got to eat a lot of this fish soup so you wouldn’t have a hangover the following morning. The following day I’d spoke to my partner, my wife and I said, “Thank God we’re going to the monastery today because I really need a break from all this heavy drinking”. We got to the monastery, we met the Abbot, he was really nice, he said “Look why don’t you stay for lunch”. I thought great and as we were walking towards his house in the monastery complex. He said, “Oh I must show you our cellars”. Little did I realise you know what he meant by that, it was the wine cellars. He insisted that we have a little drink from each one of the barrels that was maturing so yet again there wasn’t a day off from the heavy drinking.

T: And when you went to Transnistria did you do it in blocks?

N: No, I often go back to places but that was done in one block. A lot of preparatory work, which I do increasingly. So I had a vague idea of where and who I should be meeting, where I should be traveling, what would be interesting, what would make it a complete project.

T: When you’re prepping for a big trip like that, do you use a fixer?

N: Yes, fixers or researchers or both. It’s very important because time is often limited and so the more you can do. I mean I used to go in the past and have no idea and just discover everything, but of course you can also miss out on a lot that way. It can be really good to go with quite a bit of knowledge, you always discover new things anyway and all the best-laid plans always change so it’s a real advantage to do the research. It’s also a real advantage to have people on the ground who are prepared to help you.

T: With Transnistria for example how much time did you spend prepping the job and how much time did you spend there?

N: Well it’s interesting because working with Rory MacLean we both did prepping. He stayed longer than I did; he arrived before me and left after me, because he had lots of interviews to do and more research. That project we probably spent a year and half on before actually getting there but again a lot of the places I go to are very difficult to get to so it takes a lot of preparatory work to be able to make the contacts to get the access once you get there.

T: So it took you a year and a half of prep work, research etc. and then you were there for how long?

N: Three weeks.

T: Really? You got a lot out of three weeks I’d say.

N: Yeah, I probably stayed a few days less than that. But again the way that’d work is that I’m up before dawn and I’d work late into the night so they are really exhausting days and there’s no day off, you’re always looking, always seeing new things and always shooting.

T: With crowd funding for the book, do you use any form of social media like Twitter?

N: Not really, to be honest, I get so swamped. I never have a free moment. I have someone who comes in and helps me, not even once a week and then I’m in a fortunate position I guess because maybe there’s quite a bit of interest and traction already. But I’m not building on it or seeking it out. I suppose it depends what your needs are. For me it’s like yeah you could have hundreds of people who check into your website or Facebook or Twitter but sometimes what I often say to young aspiring photographers if you do need to have something seen it’s not necessarily the numbers of people, you might just have to have three or four people look at the work to actually get the result you need. Especially if it’s advocacy or whatever. So in my case I feel it’s very much hopefully it’s the right people who are seeing it, rather than posting something and saying I got 160 000 hits.

T: It’s a good point. With something like Twitter, a lot of people use it as a communication tool, a type of short-form journalism. If Twitter had existed when you did Danziger’s Travels, would you have used it?

N: No, for various reasons because I still don’t use it. I’m often doing very sensitive work so I can’t have people following what I’m doing because then the access would be denied and in the work I do which I hope stays the course I’m now not doing news and actualities which I’ve done. But now I’m doing work which is much more intimate. It’s also good to me to look back and see what I’ve done rather than feeding it out in a constant stream. I want the work to be seen in its entirety rather than in drips and drabs.

T: Well in that case I thought we could take it back to the beginning in a sense, talking about Danziger’s Travels which is your first book (first published in 1987, my copy 1993) I came across it when I was at college and I was fascinated by your journey, which culminated in some unbelievable experiences in Afghanistan, China and Tibet. Would it be fair to say that, that journey or journeys shaped your attitude to photojournalism? In that, without context photographs lose their ability to deliver the message intended?

N: Yeah I think so, I think I wasn’t aware of it then and I think that hopefully the photography has really moved on. But again it’s looking back and seeing the gaps and the holes and this is just the first step. From that I really really wanted to go on and refine what I’m doing and be more focused, yeah it’s taken a long time. But yes that was certainly the first step; I mean it changed my life as well in the sense that before that I was a painter. I think probably a lot of the reactions, although the book did very well and it’s still going strong, it was the first stepping-stone.

T:I’d say so, after that you did Danziger’s Adventures which was from Kabul to Miami I think.

N: Yes and then one about Britain which was important to me because after travelling to all these foreign places, a lot of comments were being made which I was critical of in terms of people looking elsewhere, I mean I could understand it, they were seeing what I was doing but I thought it would be really interesting to do what I had done elsewhere in the world in Britain.

T: That was one of my questions, with your project on Britain, which became two books, Danziger’s Britain and also The British: In Photographs. You’ve told me what inspired the project. It’s all very well saying I’m going to do a project on Britain but again that must have been a massive amount of prep work.

N: It was, I also got a fellowship from what’s now the National Media Museum, it was then the National Museum of Film, Photography and Television and I had a real idea of what I wanted to do. Sort of a road trip around the UK, it was research, It was looking at the UK and wanting to go to different regions, cities, towns, rural areas so trying to find contacts in different places that would give me the access, the variety, the help Everything I do is really teamwork even though it was me doing the writing or taking the pictures, it was a lot of prep work. Again there was so much more than anything you see in the books, you know when you’re editing images. Equally for the text I went to many more places.

T: We’re talking about mid-nineties aren’t we?

N: Yes

T: Before the Internet became really big, so you were before email?

N: Yes

T: So lots of phone calls then?

N: Phone calls, lots of fixed line phoning. In fact some of the neighbourhoods I had to visit before they would let me in so that was interesting, with no camera etc. etc. I subsequently went on to make a documentary film series, actually going back to some of those areas but shot in black and white. The documentary films were actually composed of 90% stills. I’m still really attached to doing stuff in Britain like that but there’s very few magazines willing to commission that kind of work now.

T: Moving on slightly, with your project 30 Days you managed to get behind the scenes with Tony Blair and his cabinet during 2003 (the run-up to the Iraq war). How did you get the access and what triggered the idea to do a project on him?

N: The access was completely out of my hands, The Times Magazine organised the access and in fact they asked if I was free to do two or three days a week for two or three weeks because it was coming up to his (Tony Blair’s) 50th birthday. No one was aware when all of that was put in place that it was going to be the lead-up to the launching of the war in Iraq and, in fact after the first day they kind of said ‘have you got everything you need?’ because I was already asking ‘Can I come back tomorrow?’. I was asking what’s happening tomorrow? ‘Oh he’s going to launch the Middle East Peace Plan, he’s going to speak to Yasser Arafat.’ I said great. So I came back the next day, that was a Friday, so I said what about tomorrow, Saturday, it was a weekend.They said ‘Don’t you want to go home?’ 30 days later with the most extraordinary access but obviously they thought, you know, they were going to win the war then.

T: You were a trained artist, trained at Chelsea Art School, you were going to become a painter but suddenly photography got in the way. At what point did you pick up a camera and think this is for me, this is an ideal way for me to communicate my ideas.

N: It was evolutionary I think, there wasn’t one moment. As a kid I had a camera, enjoyed watching football games and it was a way of getting into the grounds without having to pay to get in through the turnstiles. I suppose I realised then that being a press photographer gave you access to extraordinary places that you couldn’t otherwise get to, particularly then when you’re young and you haven’t got the money to do a lot of things. I think after that, I did want to go back to painting after my first book. With Danziger’s Britain in fact I didn’t take up photography as it were professionally then and it slowly evolved whereby I wanted to go back to places, in fact I was commissioned to go back to places, initially when Saddam Hussein was gassing the Kurdish population and bit by bit it became a tool to kind of go back to places I’d visited before and I realised you know, this is where I want to be, this is what I want to do. And although I’ve written the books, made many many documentary films, I’m happiest behind the lens of the camera.

T: So with Adventures in Transnistria, Rory does the writing and you concentrate on what you love doing most.

N: Yeah it’s interesting. My first documentary film I was there doing everything, which is what you’re told and taught to do now, which is you know sound, the picture, the editing. You name it, there’s nothing left for anyone else because you have to do it all. And I’ve gone the other way because my first documentary film, which was a BBC video diary which was shot in Afghanistan, there was no one doing the sound or what have you. I did have someone helping me locally, occasionally if I need his help. But now I don’t want to do several different things at the same time, if you’re really concentrating on the imagery, it’s really difficult to hear what’s going on. You do but at times it disappears because you’re so focused. None of my images are cropped, none of the black and white images are cropped and if a colour image is cropped it’s because of a very specific reason and we’re taking one in every 300 images, if that.

T: You’ve won plenty of awards, World Press Photo for example .But what keeps you going, taking pictures and coming up with new projects?

N: Well I love what I do. I think it’s an incredible privilege. I love meeting people. I’d say I like going to new places but equally I like going back to the same places because the experience is richer and richer each time you go back and I feel really privileged because most of the people I’m photographing don’t have anywhere like the kind of opportunities and possibilities that I have. I think if I’m able to give a voice to people who deserve to be heard then if I can do that, great.

T: Which images mean the most to you out of everything you’ve photographed?

N: I’m always dissatisfied, I take a picture and I’m always, I should have done this, I should have done that. I didn’t get this, I didn’t get that. Because I’m often dealing with dark parts of life, images where there’s a lot of joy and happiness are good, it pleases photo editors. I think because people forget that in every situation and in the most difficult places there’s a lot of good humour and people with very little means still have joy and happiness. I would say that the images which really stick in my mind are the people who I’ve become friends with or that I really admire because they’ve overcome huge obstacles in life; they’re survivors in the most extraordinary circumstances so when I see those pictures, I always think how lucky I am. It’s not really to do with the quality of the image; it’s more about the individual that is in the picture or the situation.

T: I suppose the emotional, the bond between you and the subject?

N: A huge huge emotional attachment. Not always because I think that would be unfair, there’s a lot of people obviously I don’t keep in contact with because sometimes you do a lot of this and you feel lucky. There are individuals that, 20 years on and we’re still in touch. It’s interesting, not just professionally, it’s lovely to see people you photograph have their own families and life moves on one way or another. Distressing when it doesn’t.

T: So in answer it’s hard for you to pinpoint one images or two images, you have so many bodies of work

N: I’m quite tortured and tormented by one: I did a project where I went back to find the same women, it’s about the effects of war on women in conflict. I found ten of the eleven women across the world which in itself was good; I had a lot of help trying to find the women. This one particular young woman called Mah-Bibi who aged 10 or 11, she didn’t know her age, was already looking after siblings, two younger brothers and I’ve never been able to find her again. You look at that image and it’s very strong because you realise that her life is difficult, I just want to know what happened to her.

T: Would you say that objectivity is over-rated seeing that photographers can’t help but form an emotional bond with their subjects? I mean a traditional photojournalist.

N: Well I originally started, as you know with no photographic training, no journalism training and it was always, you have to be objective, There are two sides. And that’s certainly from Afghanistan where I travelled with the Mujahedeen, the so-called holy warriors against the Soviet Union and I was very much horrified by what I was seeing. But on reflection, I didn’t realise actually what life was like for women in Afghanistan when these freedom fighters were fighting for freedom as it were. It wasn’t for freedom of women and then going to the government side. Like many in the west, I didn’t see the whole picture. I think there’s something between being objective and looking at the situation beyond what’s in front of your nose. You need to analyse and be critical but I don’t think you necessarily have to be, there’s right and wrong in a lot of these situations. So in that sense when I’m taking pictures of something that might disturb people then it’s because it is disturbing and I don’t think we have to objective in that kind of situation.

T: When you were travelling, you were documenting what was going on around you; it must be difficult to see the bigger picture when you’re doing a project like that.

N: What I would say is that now I’m not trying to give the big picture, in the past I would have thought this might stand up but life is so complex and so difficult I’m just trying to look at snapshots., something that might give you a picture. Certainly it’s not, like I’m trying to describe or show the entirety of what’s taking place.

T: But these people were looking after you as well

N: Everywhere I’ve gone, most people in most places. As I said as one point it’s been teamwork and you can’t produce quality work unless people are really accepting of you. If they have been accepting of you that usually means they’ve been a major part of helping you, trusting you etc. The least you can do is try and repay that. I’ve often failed, some people have been upset. Maybe an image, images or a story but I’ve tried to be as straight as possible. Trying to represent them in what I think is the right light.

T: Following on from that, would you say that relationship building and how you get on with people is as important as the pictures you take?

N:Totally, in my case people would say it’s all about relationships. The technical aspect, you can’t quantify it but it’s only a tiny percentage. You’ve got to know what you’re doing but it’s no good knowing what you’re doing and not having a relationship because you won’t get the images. It’s no good going out and buying the best camera; the best camera’s not going to get you the best pictures because it’s you that gets the best pictures.

T: if you were starting out now in your career, would you do anything different?

N: Difficult, now having seen the world would I have become a photographer? Probably, maybe not the most helpful thing you know. I don’t whether medicine or law or something else, I love the visual arts and I wanted to be a painter. For me certainly the black and white is like sketching, the images I’m trying to compose I feel very comfortable with it. I don’t think there’s technical or photographic things I would change, would I have chosen a different career, well maybe. I’m not sure it was the most useful thing or profession I could have done.

T: Isn’t it true that a lot of visual artists have that, a sense of guilt about what they do?

N:I haven’t spoken to you enough about that particular thing, guilt. Yeah sure you see these things and you wonder about the usefulness of taking another picture all of us will say a mere drop of what we shoot is actually published and again how much can be said about the story because space is limited so you don’t necessarily see the richness of being in a place and seeing it is one thing. We when we visit, our experience is limited but then the person who reads it is even more limited. We’re all privileged when we do this as photographers to be able to show something of the world. The world that we live in.

T: Do you think now with the fact that you can just self-publish, you don’t have to go through the traditional channels of say getting a commission through a newspaper or a magazine or a TV station or whatever else? Assuming you can find funding for it or funding it yourself, you can do it yourself, publish it yourself, release it yourself through the Internet.

N: Well it’s more democratic, in the sense that we can all do a lot more than we used to be able to do. You don’t need a lot of money to shoot a video, edit and upload it but I think what’s interesting about that is how many people are watching it. You only need to affect one person, great but look at the quantity of what we have out there which also in a way diminishes a lot of things that do have quality and really speak out. We all want to believe that hopefully quality rises to the top but I think sometimes you need to get hold of the fact that it’s not the amount of people that go on your website but who are the people going on your website and then what do they do with it. I’m very focused on that, we all think isn’t it great and I can see that on my website. You do a programme, you’re invited to an interview on BBC radio say and you suddenly get a mountain, a spike of hits. You know at least people have listened, you’ve caught their attention and they’ve gone and looked further into it. I worry about young people getting carried away about uploading everything. It’s important that everything isn’t instantaneous, you need time for reflection.

T: Okay last question is what would you advise to a photojournalist starting out in their career now?

N: If they want to be a photojournalist probably the most important thing is that they try and put together a project that they’re passionate about, that they’re interested in and spend a lot of time on it and keep reworking it, keep looking at those images. Be supremely critical and again back to some of the things I said earlier on. It’s not the quantity, if there’s anything there’s any doubt about, take it out of the final set and keep refining it. Keep going back and keep working on it.

www.nickdanziger.com

http://unbound.co.uk/books/back-in-the-ussr

Nick has a quite extraordinary exhibition on at the British Council about North Korea called Above The Line. It’s on until 25th July. Worth checking out.